Described as "nothing short of revelatory", the production of this play achieved milestone status in the first week of the run.

Contemporary in feel, classic in its minimal execution, and chock full of performances which flip the switch of the electricity of theatre.

Branagh reaches Richard's twisted and tormented soul, and gives us the full scope of the tragedy of this man's inner workings.

Kenneth Branagh Returns to the Stage in Richard III

The 2002 production of Richard III starring Kenneth Branagh opened at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield and closed on April 10, 2002.

Reviews below from Variety, the Herald, and the Yorkshire Post. Enjoy the excellent program notes from scholar Russell Jackson

on the production mounted by Michael Grandage. Also the cast list, information on the play, and a bit of Richard's opening lines.

"Take up the sword again, or take me up."

RICHARD III

Variety

March 2002

Matt Wolf

SHEFFIELD, ENGLAND -- Crucible Theater, Sheffield, production of the

Shakespeare play in two acts, directed by Michael Grandage.

Sets and

costumes,Christopher Oram; lighting, Tim Mitchell; composer, Julian Philips;

fights,

Terry King. Opened, reviewed March 19, 2002. Running time: 3 HOURS.

Richard III ..... Kenneth Branagh

Queen Margaret ..... Barbara Jefford

Clarence ..... Gerard Horan

Duchess of York ..... Avril Elgar

Buckingham ..... Danny Webb

Lady Anne ..... Claire Price

Queen Elizabeth ..... Phyllis Logan

Hastings ..... Jimmy Yuill

Edward IV/Ely ..... Richard Durden

Grey/Richmond ..... Gideon Turner

With: Mark Bonnar, Robert Demeger, Elliot Jeffcock, Andy Hockley, Robert East, Michael Jenn, Tom Mullion, Jonathan McGuinness, Ryan Sampson, John Tierney, William Rycroft.

Shakespeare's envenomed Richard strips himself naked --- emotionally speaking --- in the opening soliloquy of "Richard III," so why shouldn't Kenneth Branagh's remarkable "foul toad" first appear before us attired only in underwear, Richard's misshapen body literally stretched out on what seems to be some kind of rack? The opening of Michael Grandage's new production of this often produced yet rarely satisfying play makes the audience sit up, and it's to the credit of a creative team firing on all cylinders that the interpretive excitement rarely abates. We all know that Shakespearean drama's most renowned "hedgehog" (in the final scene, Branagh is even dressed as one, albeit in Liberace-style flaming red) can be funny and fierce, but I've never before clocked a Richard so consumed by pain. "There is no creature loves me," he cries, determined as a result to engender hate. And as Branagh speaks the line, his delivery totally lacking in self-pity, the play takes on a newfound sting,as befits a ruler who has spent a life on the rack, psychically speaking, well before Grandage's fearless imagination places him there.

"Richard III" was more or less sold out prior to its press night at the Crucible Theater in Sheffield, south Yorkshire, the same venue where Grandage --- the theater's associate director in charge of programming --- lured Joseph Fiennes to play Marlowe's Edward II this time last year. And while it could be argued that bagging Branagh for his first stage role since starring as a decidedly dry Royal Shakespeare Co. Hamlet a decade ago marks an arguably greater coup, no casting gambit really matters if you don't deliver the goods. Branagh et al. succeed not so much by reinventing the play --- the production is far less radical, for instance, than the Richard Eyre-Ian McKellen version that subsequently fueled McKellen's filmed "Richard III" --- but by investigating it truthfully from scratch. The result: a character famed for possessing an arm like a "blasted sapling" is seen to have a soul like one, too. Suffice it to say that as a "foul defacer of God's handiwork," Richard acts from experience as aman whom God long ago defaced.

It was pretty much a given that Branagh could handle the verse. The play's actorish comedy emerges easily and sometimes with bruising force --- the quickdismissal of Richard's "He cannot live" to an early victim: No crisis of conscience there! --- while his admission to himself that "Sin will pluck on sin" suggests the actor as a potentially mighty Macbeth. More surprising are the currents of feeling, coupled with an unusual degree of bodily self-disgust, that exert a perverse fascination beyond even Antony Sher's celebrated crutch-wielding perf of the same role in 1984. Stripped of the garments that camouflage his disfigurement, this Richard isn't the hunchback of legend but apasty figure, at once stooped and sad, with a putty-like physique that demands of Branagh a series of punishing contortions in order to bring home the severity of Richard's physical estrangement from his own self.

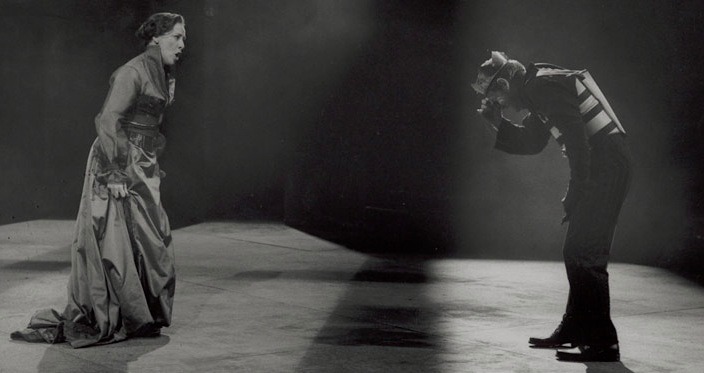

For much of the play, Branagh walks the stage with one leg encased in a contraption , which is why it's a particular shock when he drops to the groundto crawl after Queen Margaret (the supreme Barbara Jefford) seeking repentance. Or, earlier on, hurls off him the young lords whose lives he will later cut short when they dare to roughhouse with so wretched a specimen of flesh. And though his left arm lies limply by his side, Richard's right one is at the perpetual ready for a fight, with Branagh snapping to physical life just as startlingly as he allows himself to droop --- as if the sheer price of playingthe rampaging ruler were worming away at Richard from within. (Remarking "I am not in the giving vein," he hurls Buckingham to the ground with just his good arm.)

So revelatory is its central performance that one risks overlooking the able support of a distinguished cast, among whom Jefford (Ralph Fiennes' recent, and no less peerless, Volumnia) sets herself apart as a trembling termagant of the highest order. If the other women aren't in her league (Avril Elgar's Duchess of York is especially pro forma), the men are excellent down the line. Danny Webb's Buckingham makes an unusually moving cohort-turned-victim, his realization that All Soul's Day is also his own doomsday coming too late to help. Among an ensemble made up to some degree of longtime Branagh colleagues, Gerard Horan (Clarence) and Jimmy Yuill (Hastings) remind us that what can sometimes seem like thespian clubbishness has a basis in reason: Both men are very good.

Still, it's hard to imagine attention placed anywhere else once Branagh stalks Christopher Oram's sparely appointed stage, lit with its own distinctive bite by Tim Mitchell to the alternately ceremonial and elegiac strains of Julian Philips' original score. This play is popular in the same way that villainy (especially in the theater) so often is: Richard III is the malformed miscreant you love to hate. How often, though, is a character's external capacity for the horrific achieved without sacrificing a sense of the pain that begins within? Let's hope it isn't another 10 years before this actor --- here playing a character "made blind with weeping" --- leaves a Shakespearean perennial looking blindingly new.

_____________________________________

Richard III, Crucible, Sheffield

The Herald

21 March 2002

KENNETH Branagh's Richard III may not be the most fiendish you'll ever see - Antony Sher's scurrying, crutch-hopping black beetle and Ian McKellen's blatantly fascist dictator take prizes for that. But on his return to the stage after a decade, Branagh certainly takes Michael Grandage's new production of Richard III by the scruff of the neck and wrings fresh wonders from it.

Here is Branagh like we've never seen him, painfully naked in his emotional openness, if still the commanding presence we've come to associate with his Henry V and recent tv appearances as Shackleton and Nazi henchman Reinhard Heydrich. Branagh is a born leader, which makes him a natural for this most maligned but popular villain, who cheats and murders his way to the English throne. Branagh and director Michael Grandage, who is to take over from Sam Mendes at the Donmar, also find a sensationally arresting visual metaphor for Richard's disturbed personality. This Richard's relationship with his physical deformity is a case of arrested development, with Branagh pinned to a contraption in a pose somewhere between mental patient suffering electro-convulsive treatment and Christ on the cross. It is a performance of dizzying energy and manipulative prowess, with Branagh spinning instanteously from tearful plaintiff to sardonic, cold-hearted killer and the Sheffield audience took him to their heart.

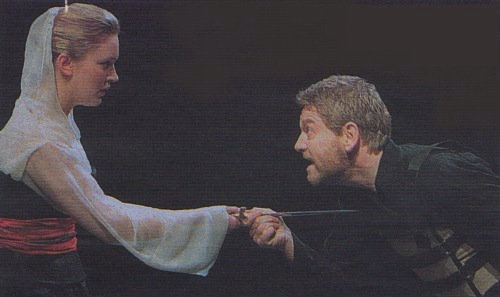

Grandage's impressive production, with its grey stone pillars and slanting medieval light, surrounds him with fine support, not least from Phyllis Logan as Edward IV's unfortunate widow, Elizabeth, Claire Price as an unusually credible Lady Anne and Barbara Jefford's strongly spoken but far too sensible cursing crone, Queen Margaret.

The evening though belongs to Branagh. He's a knockout.

_____________________________________

Richard III, Sheffield Crucible

Yorkshire Post

March 2002

Lynda Murdi

It was almost a foregone conclusion that Kenneth Branagh would be good as Shakespeare's evil monarch. But is he great?

Certainly. I can't think of another actor currently of suitable age who could give as impeccable and impressive a performance. But whatever their skill, people with exceptional talent outstrip everyday criticism. Instead, they enter a generational league such as: is David Beckham better than Stanley Matthews? The question now is: how does Branagh rank against legends? After his Henry V, he was compared to Laurence Olivier who also gave what many believe to be the definitive interpretation of the Bard's "bottled spider".

Since then, Antony Sher and Ian McKellen have both turned in exceptional performances. They all presented startling images as the witty and evil hunchback, the scuttling misshapen creature on NHS crutches, the fascist leader.

Directed by Michael Grandage, associate director of Sheffield Theatres, Branagh brings us the baby scarred at birth, the physically vulnerable disabled human being, rolling on the floor to get dressed and needing support from a corset and leg calipers to stand.

His first entry is a surprise. He is wheeled onto the dark, inhospitable stage wearing only white underpants (it would make better sense if he were totally naked--but that would indeed be a sensational move for such a superstar). He is lying on a sort of stretching rack which looks like a Heath Robinson instrument of torture but is, presumably, meant to be the 15th century equivalent of a homecare medical aid. Prone, Branagh begins the famous opening speech, "Now is the winter of our discontent".

This is the first reminder that theatre has been the poorer for his absence.

His best actor's tool is his voice, blessed with a huge range and dexterity of delivery. As Richard murders his way to the top, he employs it to full advantage, coaxing clarity and layers of meaning from every line. He never loses an opportunity to relish his character's ironic humour, his mocking pride in his manipulative duplicity bringing contemporary vocal inflections to the text and earning a more than usual number of laughs. When mobile, Branagh limps stiff-legged at an arachnid's urgent speed, using one arm to gesture animatedly as the other hangs limp and bound. He's as genial as a party host when meeting other nobles but clearly a bit of a tricky Dicky when instructing henchmen.

The first half lasts one hour 50 minutes, by which time I judged Branagh to be very good, very thorough but not great. In my own opinion better than Sher, who tried a little too hard, but not as electric as McKellen. (I was born too late to see Olivier on stage, alas).

Then something remarkable happened. Once crowned, Richard became ugly. As Branagh's face changed, so did his demeanour. His villainy and vulnerability struggled to gain ascendancy.

Visual expression was later given to those two qualities by his extraordinary battledress. Edged along his back by skeletal spine bones, it suggests aggressive armour while being redolent of spina bifida.

Suddenly, this actor was as transfixing as any could possibly have ever been. So, if not truly great overall, then Branagh was well on the way to achieving greatness by the end of the run.

There is, of course, much more to Richard III than the central character. But however brilliant everything else may be, the play always tends to flag whenever he is off stage. There's no getting away from scenes where nobles stand around in groups trading names in a confusing way. But Grandage brings a sense of sweeping momentum by swiftly juxtaposing such large-scale scenes with smaller, intimate ones. This director's high-quality production values have now become a house-style for Shakespeare at the Crucible. As in last year's Edward II, which starred Hollywood's Joseph Fiennes, Tim Mitchell uses lighting design to astounding effect. There's no need for scenery, other than the backdrop of monumental stone pillars, when Mitchell can create such atmospheric spaces. They include a red-bathed Bosworth battlefield where hand-to-hand fighting takes place in thrilling style.

Among a cast of 20, Danny Webb skilfully makes Buckingham akin to a modern-day, self-serving political chancer. His is a very natural performance, contrasted by the equally admirable, but more conventionally theatrical, style adopted by Barbara Jefford as the increasingly enraged Queen Margaret. Other powerful support is provided by Phyllis Logan as Queen Elizabeth, mother of the murdered princes, and Claire Price as Lady Anne, wooed by Richard over her husband's corpse. But, however talented the other actors, this production, happily staged in Yorkshire and not London, is really a case of Branagh's back. Sound the trumpets. And queue for a standby seat.

_____________________________________

The Guardian

Wednesday March 13, 2002

Angelique Chrisafis

After 10 years in films, Kenneth Branagh makes his stage comeback tonight - in a part-time Sheffield snooker venue, best known for hosting Steve Davis in the world championships.

Branagh is playing Richard III, Shakespeare's misunderstood villain, at the Sheffield Crucible - a move which reinforces the shift in audience attention from London's West End to the regions. Theatres outside London are yet to see a penny of the promised £12m to help them this year, but many shows are selling out faster than West End productions.

Richard III is the fastest-selling production in the Sheffield theatre's 30-year history. Its run has been extended to take in increased demand from US and Japanese visitors. "We couldn't lengthen the run any more than four days because we had to set up for the snooker in April," a spokesman said.

Branagh follows Joseph Fiennes, who turned down film offers to play Marlowe's Edward II in Sheffield last year. Grahame Morris, Sheffield's chief executive, said: "The real significance of an actor of Branagh's calibre choosing Sheffield for his return to the stage is that it shows that London theatres no longer rule the roost."

Branagh, who is to star in the second Harry Potter film, is believed to have been attracted by the prospect of performing to a younger audience.

(Thanks to Toni)

_____________________________________

THE TWO PLAYS OF RICHARD III

By Russell Jackson

Richard III does not tell the truth - or the whole truth - about historical events. It accepts and develops the darkening of Richard of Gloucester's character that favoured the Tudor dynasty's reputation as direct and legitimate inheritors of Richmond - the man who saved the realm from a monstrous tyrant and murderer. None of Richard's skills as a monarch or his accomplishments as a person get a look-in, and no alleged crime is left out. The play does tell a number of truths about history, though. Richard gets power by calculated acts of brutality, but he uses the weaknesses of others to achieve them. He trades on the vanity, ambition and overconfidence of a series of accomplices, disposing of each of them when he no longer needs them or - in the case of 'deep, revolving, witty Buckingham' - when the qualities that have been so useful to him have become dangerous. When Richard is alone in his tent, he has reached a lonely eminence: 'Richard is Richard' and none of the faithful helpers waiting within call outside the tent can save him from the fearful dreams in which the conscience he has scorned visits him.

In Richard III two plays of different kinds run alongside each other. One is a historical chronicle, with a sense of scores to be settled and past crimes that must be expiated. In this scheme of things, Richard is a monstrous prodigy of evil, a scourge visited by God on the human race. Queen Margaret, like a one-woman chorus, stalks (unhistorically) through the court of King Edward, refusing to allow anyone to forget the bloodshed of the Wars of the Roses. Audiences who have seen the three parts of Henry VI may have a stronger sense of the wrongdoings of most of those Richard has killed, but this play leaves no doubt as to the general mayhem that preceded the events it shows. When the two princes have been added to the list of Richard's victims, Margaret joins her voice to those of Queen Elizabeth and the Duchess of York:

I had an Edward, till a Richard kill'd him;

I had a husband, till a Richard kill'd him;

Thou hadst an Edward, till a Richard kill'd him;

Thou hadst a Richard, till a Richard kill'd him ....

By this point, the 'troubler of the poor world's peace' (one of the kindest things she says about Richard) has in fact reached the highest point of his career. 'Now prosperity begins to mellow, / And drop into the rotten mouth of Death.' Richard's attempt to woo her mother for Elizabeth's hand is hardly successful, even if he tries to convince himself that he has prevailed. Each of Richard's adult victims has a speech reflecting on their crimes and on the power of Margaret's curse. By the end of the play his work of God's scourge is complete, and Richard himself is disposed of. A soldier who never stops invoking divinity has. purged the guilt of earlier crimes from England.

The other play contained in Richard III is a personal tragedy, with an exhilaratingly villainous hero whose vigour and resourcefulness engage the audience at the same time as they ensnare his victims. Like two of the other great figures of the Elizabethan tragic stage, Marlowe's Dr Faustus and Tamburlaine, Richard possesses a defiant, aspiring spirit. It is Richard's voice that begins the play, sardonically distancing him from the 'glorious summer' of apparent peace and harmony, soliciting (or commanding) complicity in the plots he has laid and intends to lay, and celebrating his deviousness. Richard's infirmity, treated by him with venomous humour, could be read in his own day and Shakespeare's as a sign of inward evil, but it is the strength of Richard's response to that reaction (even dogs bark at him as he passes) that dominates. Better still, he is a fine actor, who can counterfeit the deep tragedian.' In every situation, and with every accomplice, Richard is convincing. Sometimes he even astonishes himself. Against seemingly impossible odds he obtains the goodwill - and presently the hand in marriage - of Lady Anne. 'Was ever woman in this humour wooed?' In dealing with public opinion - as represented by the Mayor and citizens of London - Richard and Buckingham stage-manage a national crisis, followed by an elaborate show of pious reluctance on Richard's part when the city authorities have come (with some prompting) to beg him to accept the crown. When Richard has achieved the throne, he still needs to secure his position by having the princes killed - a crime which is represented as the ultimate evil (Clarence, Hastings and Buckingham have no great claim for sympathy) - and which seems to precipitate his downfall. By the time he reaches Bosworth Field, Richard's regime is falling apart. After the fearful ordeal of his nightmare, he encourages his troops entirely by appealing to xenophobic contempt for the enemy:

A scum of Bretons and base lackey peasants

Whom their o'ercloyed country vomits forth

To desperate adventures and assur'd destruction...

There is still an element of epic defiance in 'Amaze the welkin with your broken staves!' and 'A thousand hearts are great within my bosom.' Even in death the king 'enacts more wonders than a man' like the murderous supernatural creatures in a horror film, it takes little short of a miracle to kill him.

The play ends by bringing the retributive chronicle and the personal tragedy together. Richard's nemesis is not so much Richmond as what he stands for, a force of goodness that will heal the England that 'hath long been mad and scarr'd herself.' Richmond's concluding speech ends with the claim that 'Now civil wounds are stopp'd, peace lives again' and he urges his hearers to pray that peace will 'long live here.' It answers the play's opening lines, in which Richard mocked the false peace brought by Edward, 'this sun/son of York.' At the same time it imposes a duty: nothing short of divine intervention dea1t with Richard, nothing less will secure peace.

Russell Jackson is Reader in Shakespeare Studies at the University of Birmingham and Deputy Director of the Shakespeare Institute, the university graduate centre for Shakespeare studies in Stratford upon-Avon.

________________________________________

Kenneth Branagh will play RICHARD III for Michael Grandage at the Sheffield Crucible - Wednesday 13 March to Tuesday 10 April 2002. Press night is Tuesday 19th March. The Box Office number in the UK is 01144 2496000.

Here is a partial cast list:

Kenneth Branagh - Richard Duke of Gloucester, later King

Barbara Jefford - Queen Margaret

Gerard Horan - George, Duke of Clarence

Jimmy Yuill - Lord Hastings

Robert Demeger - Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Richard Durden - King Edward IV

Danny Webb - Duke of Buckingham

Claire Price - Lady Anne

Michael Jenn - Sir William Catesby

Mark Bonnar - Sir James Tyrrel

In Al Pacino's film "Looking for Richard", Kenneth Branagh appears briefly, explaining iambic pentameter, but alas, without dancing to it, as he does in his own film version of Loves' Labours' Lost.)

Branagh also delivers the opening speech in the Naxos audio version of the play, available at your local library.

A goodly portion of that opening speech from Richard III:

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York;

And all the clouds that lowered upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.

Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths,

Our bruised arms hung up for monuments,

Our stern alarums changed to merry meetings,

Our dreadful marches to delightful measures.

Grim-visaged war hath smoothed his wrinkled front,

And now, instead of mounting barbed steeds

To fright the souls of fearful adversaries,

He capers nimbly in a lady's chamber

To the lascivious pleasing of a lute.

But I, that am not shaped for sportive tricks

Nor made to court an amorous looking-glass;

I, that am rudely stamped, and want love's majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph;

I, that am curtailed of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time

Into this breathing world scarce half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them -

Why I, in this weak piping time of peace,

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun

And descant on mine own deformity.

And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days.

Plots have I laid, inductions dangerous,

By drunken prophecies, libels, and dreams,

To set my brother Clarence and the king

In deadly hate the one against the other;

And if King Edward be as true and just

As I am subtle, false, and treacherous,

This day should Clarence closely be mewed up

About a prophecy which says that G

Of Edward's heirs the murderer shall be.

Dive, thoughts, down to my soul....

Richard III is the second largest role in the plays of Shakespeare, second to Hamlet in the number of lines.

The story of Richard's life as told by Shakespeare derives largely from the accounts given by Sir Thomas More in his "Life of Richard the Third" published in 1513, and Polydore [How's that for a first name?] Vergil's "Historia Angliae" published in 1534. Both authors painted a rather grim picture of Richard, and these accounts were used by the chroniclers Hall and Holinshed. Shakespeare also may have used an earlier play, The True Tragedy of Richard III (printed in 1594) in his work. In that play, you can find the following call: "A horse, a horse, a fresh horse!" Not quite the same punch, is it?

Richard III is said to be actor Richard Burbage's favourite role. Burbage (1567-1619) gave the first performances of most of the plays of Shakespeare, and is credited with the first Richard III, Hamlet, Malvolio, and Othello. Burbage headed the company of players at the original Globe Theatre (1599-1613). The very first, earliest recorded performances of Shakespeare's plays, however, were staged at the Rose Theatre in 1592.

Among the actors who have played Richard III after Burbage are: David Garrick, John Phillip Kemble, Edmund Kean, Henry Irving, John Barrymore, Laurence Olivier, Anthony Sher, Ian McKellan. Kenneth Branagh joins this impressive company.

More recently, Kevin Spacey and Mark Rylance have given us memorable stage performances. Kevin Spacey relentlessly mined his "House of Cards" persona of the purely ambitious politician, while Rylance gave us an all-too-human apologetically fickle tyrant, one part fool and three parts flawed.

_____________________________________

June 2014 Update: Sir Kenneth Branagh realizes his elemental Macbeth, in Manchester and New York City. Our Macbeth review here.

![]()

FRONT PAGE

News/

The Good Bits![]()

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE

![]()

THE HAMLET PAGE

![]()

links/LINKS

![]()

What's Up: STAGE

![]()

What's Up: BOOKS

![]()

What's Up: MUSIC

![]()

What's Up: FILM

![]()

Fictional Characters

![]()

What's Up:

ART![]()

Today's Special

![]()

Sure We

Thank You