Reviewed by Renie Pickman-Thoon

A nave of mud. An apse bejeweled with candles. A crippled crown fire wall.

Above all, and below, darkness.

These and other visceralia are the marks of Macbeth, as realized by Sir Kenneth Branagh and Rob Ashford in what must be termed a perfectly elemental interpretation and adaptation. The setting, the chosen icons of symbolism, and the feeling of being part of what is happening—right there—mean a closer connection to the play and a more complex relationship with it, and the actors whom you come to see more clearly in the dark.

Secrecy was part of the intimacy. The Manchester International Festival venue for the play was shrouded in secrecy, and proved detection-proof until the very final days before the first performance (despite attempts to sleuth the locale—it’s turns out there are a lot of deconsecrated churches in Manchester). Saint Peter’s at Ancoats is a red-bricked deconsecrated church, refitted inside with several sections of wooden stands of raked wooden benches, set end to end as if watching a parade.

Guests were assembled at another secret locale—revealed in private email—Murray’s Mill which was filled with MIF volunteers who shepherded clans of ticketholders by clan name (Caithness, Fife and the like) to the entrance. Passing through the church door, and then past an actors’ walkway to the right, up a metal scaffold, to walk along a catwalk before funneling down to rustic boarded planks. Once seated, we faced opposite a bank of four rows of 28 guests, with a single string of guests fringing the upper walls in a fifth row as if empanelled in a jury box.

The temperature inside increased, as did the anticipation. To my left was an apse, with three tall windows, and three more above those, and from the farthest roof truss, a large carved wooden cross hanging over the lip of the apse. This was where an altar might be—and where later, a King might lay his trusting head to sleep.

As we awaited the start, a white-hooded feminine figure in the apse silently prayed, facing towards an arc of differently-sized white burning pillar candles; this staging upon entry succeeded in cementing our immersion in the church. The apparition would be revealed as Lady Macbeth, who clearly, or at least apparently, begins the play in a spiritual or religious place. Alex Kingston would reveal to us in a Q&A the next day that she was not only praying, she was “furiously trying to keep the wax from starting a fire”. This Lady Macbeth is practical and always thinking.

A dissonant low-level humming sound seemed to be coming from somewhere. Or was it imagination? It unsettled. It was-- unnatural.

Then there was a booming, a ruckus of sound.

And then RAIN.

You are sitting a mere dagger’s length beyond the reach of most of the rain pelting upon real men who are struggling just to see clearly through the downpour, let alone skillfully attacking each other in a vicious, loud, clanging, fight of broadswords. Yet there they are—and with every third clang, yellow and gold sparks fly through the air, like shooting stars vaulting into the seated clans who watch this mortal combat. And I’m not kidding about the vaulting sparks—I was hit with a burning rocket on the right side of my forehead while sitting in the fourth row. (It did hurt, but the adrenaline rush overcame the discomfort, and now I’ve got bragging rights.) The swordfights are rehearsed each day, and you can see why.

Instantaneously, the earthy muck which sucks at the feet of good men and bad becomes mud, and the tragic figures will be drawn down, down, one after another, besmirched and swallowed by the darkness below them.

Which brings us to witchcraft, and that wicked place below. The practice of witchcraft under the roof of what once was—and for us is now—a church may sound shocking. And the spectacle of writhing bodies in a fire pit may dislodge your sense of reality. Yet somehow, the core of the play’s tragedy spoke not merely from a nether-worldly curse or wicked prophesy, but in congruence with humanity’s own trip wires when we lack a solid balance. We are then no match for fire, water, earth; they demand our attention, they will call us back.

Elemental

Raw sights, sounds, and smells excite the senses in the opening of this play with a rain-soaked battle. Once experienced, it may be tempting to say that surely Shakespeare meant for this staging. The immediacy and primal nature (and yes, even the danger) activates our flight or fight mechanism. It’s here and now and things happen in such a rush. It’s the other end of the spectrum from Hamlet who thinks and thinks: Macbeth goes from a rain-soaked field, to hosting the King in a matter of hours.

Branagh admitted that he does not see the Macbeths as an evil scheming couple. He is coming back from battle. There were these weird sisters—can you believe what they said? Alex Kingston buys in, almost as if Branagh’s won a prize, and has merely to collect it--rather than murder his King. She reads the letter as she walks through mud sucking at her heels. The deed's yet to be done. He barely has time to wash up, and the King is coming over to stay the night. Make ready, and get the caterers. And he loves his wife, who loves him. Do we have enough wine for the party?

There is no intermission, for Macbeth, and wisely the production reinforces the rush to murder by denying its audience an intermission.

“Stars, hide your fires;

No stars pierce the bell-tolled night to give guidance to this Thane, already a member of Duncan’s army and inner circle and who that same day rendered a true general’s service to his King. There is a moment in the regicide on the altar when Macbeth seems to look at and recognize the life and King before him. And what taking that life will mean: a challenge to God. But in the darkness, people can’t see what they’re doing. True sight’s eyes are gouged with the midnight murder, replaced with Branagh’s waking vision of a flesh and bloodied Jimmy Yuill as Banquo who passes neatly through the dining table. His eyes see not what others see. Kingston’s pleading with the assembly to mark it not reads as the desperation which grows inside of her—that murder will out, and her husband is beyond acting any innocent part.

Once launched, there is only the unholy mission at hand, hurtling a clutch of families onto the bloody steel of ambition. Yet, not ambition so much as how one sin leads to another, must needs lead to another; the step that o'ersteps tumbles this man and woman into a place where they are wholly lost---when tomorrow brings "nothing". Not even the company of the married soul whose torture ends its own torment.

The church walls seemed to breathe, they seemed to hum. Pacing in the transverse from left to right and back again, the entire population seemed haunted, full of dis-ease, or at best not free to choose their destinies.

As the man who would be King, Branagh is genuine, friendly, strong, and a real man with real desires, sexual included. As tyrant, his fearsome power-mad trek gives the lie that he directs what deaths will follow, though the mounting murders seem to beget horrible splintered versions of themselves: blood will have blood. Fallen, his voice, gestures, and looks paint the clouds which gather above him and fill his mind. Every word delivered by Branagh is clearly spoken, and seems to have been invented on the spot. An exception is the “Tomorrow” speech, which Branagh seems to be pulling out from inside of himself, slowly, painfully, as if drawing out his essence in the form of invisible sinews, a kind of dissipation in front of us. It was so quiet in that huge church then. If you have never experienced the talents of Sir Kenneth on stage, put it on your bucket list. It’s as if he isn’t speaking aloud at all, but addressing you alone. So public and so private.

Alex Kingston is well-cast in a role which can be diminished by caricature; Kingston shines. As Lady Macbeth and her husband dis-integrate, we are struck at how each of them is now divided from themselves as well as each other. Objective reality is no longer shared, they cannot shake the altered reality of a damaged mind, a soiled soul. High up on a lonely precipitous narrow, Kingston walked and talked, without rest, employing a repetitive gesture (wash your hands, put on your nightie) as a device that took the place of her working mind. This “locked in” behavior felt both scary and suited to a mind which had snapped.

Early on, when Kingston takes Branagh's bloody hands, in the center of the nave, and they look at one another, we realize they are lost. I felt a moment of grief – it was like another fall of man. Yes, the horrors of murder in a church and the level of moral transgression had not evaporated. But, in a world where people still make bad choices—and so often—my distress for them was real, if not deserved.

There is so much more which might be remarked upon: Birnham wood advances with minimal yet strong blocking amidst a tribal beating scored by Patrick Doyle; three doors house three weird sisters whose strangled voices grate unnaturally upon the air; grief-stricken scenes from Ray Fearon’s Macduff; the ease, fluency and excellence of the ensemble of actors. The women’s performances are impressively strong and the men are stunningly gorgeous. The care and cultivation of this production are clear right down to the special type of “mud” used. A once-in-a-lifetime theatre experience, this Macbeth is a triumph of elemental story-telling.

If you are lucky enough to be heading to the Armory to see a version of this site-specific production, your sojourn lies ahead. Lucky you.

Production photos by Johan Persson

_______________________________________________

Macbeth

Park Avenue Armory, New York, N.Y

Saturday, June 7, 2014, A–5&6 (front row, Stonehenge end)

Directed by Rob Ashford and Kenneth Branagh

A clan of audience members is ushered through the heath toward their seats in grandstands alongside the set of Macbeth in the Park Avenue Armory's drill hall. It's a transformative moment, thanks to set designer Christopher Oram and lighting designer Neil Austin. Photo by Stephanie Berger, Park Avenue Armory.

We enter like Hogwarts students parading into the Great Hall, shouting our clan name, "Robertson!" assigned to us according to the location of our seats. We are led across a Scottish Highlands heath and past a full-size Stonehenge-like temple to our seats in one of two grandstands rising on either side of a long, muddy pit. Mirroring the Druid temple on the other end of the arena is another stone temple but with Christian iconography, where a nun tends to hundreds (it seems) of candles. Soon, two armies emerge dressed in authentic 11th century Scottish tartans and engage in earnest combat in that pit. You might think you've landed in a tournament at Medieval Times, until Kenneth Branagh speaks Macbeth's first line, "So foul and fair a day I have not seen."

So epic and intimate a production I have not seen. William Shakespeare's Macbeth is turned into a grand spectacle in the Park Avenue Armory's 60,000-square-foot drill hall while yet remaining a domestic noir murder, delving into the psychosis of love, ambition, and ambitious love. It's visceral battles, and it's intensely conspiratorial dialogue spoken in fluid verse. It's elaborate sets creating thematic tension, and it's magical effects rendered with simple stagecraft. It's the product of Rob Ashford, Broadway's current it director and choreographer, and Kenneth Branagh, the world's itShakespearean actor and producer, giving us great fun with performances that yet leave us emotionally raw.

This production premiered at the Manchester (England) International Festival in July 2013, using the decommissioned St. Peter's Church for its theater, but it always ultimately was intended for the Armory's Wade Thompson Drill Hall, one of New York City's largest unobstructed interiors. Ashford and Branagh have gone to great lengths to immerse the audience in the story, beyond their transformation of the drill hall into 11th century Scotland itself with Christopher Oram's set and costume designs and an atmosphere, both natural and supernatural as Shakespeare describes in the play, created by lighting designer Neil Austin and illusion consultant Paul Kieve. We receive our clan assignments and wristbands identifying our allegiance upon entering the Armory and are sent to specific waiting rooms. Our play programs are clan-specific: The Robertson Clan originated in south central Scotland, just north of Fife, and we read that we are descended from King Duncan I who ruled from 1034 until his murder in 1040. Yes, that Duncan. "Tonight, the originator of the Robertson clan meets his untimely end," our program points out in its introduction.

The cast numbers 58, of which half are the ensemble serving as monks, warriors, and servants during the play and ushers before and after. It rains during the first battle, and we in the front row, at least, get wet. When Great Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane, we can see the forest of soldiers coming across the heath. When Macbeth is humping Lady Macbeth, the two are backed up against the four-foot wall running in front of our seats and I'm so close I could flick Branagh's ear. Though I can't see exactly what he's doing with her, the audience opposite us vocally gasps. And if you happen to be sitting near where the Porter fixes his own drink, note that your own lap will suffer the literal fall-out. When the Weird Sisters first appear, seeming to float among the temple stones to our right and announce their intentions to meet Macbeth on the heath, they pronounce his name so forcefully and while pointing across the arena that we look to our left and, suddenly there, Branagh is poised with sword in hand on the church steps. The audience is too shocked to even applaud the star's first appearance (bless you, Branagh). Thereafter, we frequently glance toward one end of the stage or the other when a character's glance or gesture leaves us expecting to see some instrument of evil or good magically appear, instilling in us a palpable sense of the supernatural and a paranoia that grounds Shakespeare's lines in our inner selves.

One key to carrying out intimate and introspective moments in such an arena production is the blocking. The actors never stay still for long, constantly moving up and down the lists. Credit sound designer Christopher Shutt, too. The actors wear microphones but don't sound like they are miked (in contrast to Public Theater productions at Central Park's Delacorte Theatre), and sound effects and Patrick Doyle's score are sublimely mixed so as not to overwhelm the dialogue.

Ultimately, that is what a Shakespeare play is all about, the language. You can count on Branagh and any cast he assembles to deliver the goods (and the evils, for that matter, when appropriate). This is the fourth time I've seen him live (and I've seen all four of his filmed Shakespeares), and his command of Shakespeare's verse is perfection to my ears. He maintains the poetry of the verse structure without sounding poetical and speaks the rhetorical passages with natural ease, each word infused with energy, even in his characters' most introspective moments, creating vivid elocution. For me, always on paper and often on stage, the language of Macbeth is among Shakespeare's most obtuse; but not in Branagh's delivery, and the whole cast follows his lead.

The action plays out in the tension between Christianity at one end and a pagan spirituality on the other. The witches' domain is obviously the stone temple, though they wander onto the main playing area for the murder of Banquo and the apparitions (presented by actors emerging one by one from a large sheet undulating like a boiling cauldron). On the other hand, the Scots generally enter from the Christian end. Branagh makes two notable alterations to Shakespeare's original script (the Hecate portion, believed by scholars to be a post-Shakespeare interpolation, also is excised). First, he cuts the expository Act One, Scene Two, and replaces it with the actual battles being described there. Why not? At his disposal is a faux battlefield inside a real military fortress and a couple of dozen soldiers with which to wage war. He also enacts Duncan's murder in full view of the audience, not offstage. Argue whether this undermines Shakespeare's dramatic purposes if you will, but it does suit the thematic aesthete of this production, especially as the king's bedroom is placed in front of the Christian altar.

It's also notable that not only does Macbeth first appear at that end of the stage, but also that the nun tending to the candles turns out to be Alex Kingston playing Lady Macbeth. As her Lady Macbeth reads the letter from her husband, she moves to the center of the arena exhibiting unhindered excitement. She then learns of the king's approach and begins to formulate what might happen "under my battlements." She pauses, looks tentatively toward the pagan temple, and drawing a circle around herself in the dirt she speaks her incantation: "Come, you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here and fill me from the crown to the toe top-full of direst cruelty." We can't help feeling the potency of her pagan prayer; Christian redemption doesn't hold a candle to it.

Lady Macbeth here is overcome with the rush of love. Between them, Branagh and Kingston create the most happily married couple in the canon. However long they have been betrothed, they have quenchless passion for each other, a lust bred of true love, a mating of souls as well as bodies, hearts as well as heads. Branagh's Macbeth, returned from the wars, is already unbuckling as he strides toward his wife (he knows Duncan and company are fast approaching, so he hasn't much time—even if he could endure one more second apart from his wife's touch). When Duncan does arrive and Lady Macbeth comes out to greet him, she is still pulling her gown up over her shoulders, and her attendant gentlewoman (Katie West) buttons up the back of the gown as Kingston delivers Lady Macbeth's welcome.

Branagh's Macbeth is not necessarily harboring thoughts of regicide after his encounter with the Weird Sisters, but he is calculating how he could "o'erleap" his way to the crown. Duncan, you see, is no doddering saint of a king. As played by John Shrapnel, he is a bowling ball of a warrior leading a loose federation of tribes toward some concept of national security. He's both brave and gregarious with a bearing that inspires fealty and fear in the thanes.

In fact, the most significant thing Macbeth does comes between Scenes Three and Four in Act One: He writes his wife, his "dearest partner of greatness"—Kingston positively shivers when she reads that description—"that thou mightst not lose the dues of rejoicing by being ignorant of what greatness is promised thee." When Lady Macbeth asks her husband when Duncan "goes hence," Branagh makes clear in Macbeth's answer that murdering the king is not on his mind, at least certainly not that night when he is a guest in their home. Lady Macbeth, meanwhile, has made clear in her earlier soliloquy that foremost in her mind is her husband's chance at greatness, which she feels he deserves sooner than later, and she knows his own sense of honor is the only real obstacle that needs o'erleaping. In their state of love, so wholly devoted to each others' happiness and wish fulfillment, they get swept away in the tide of opportunity, thrusting them to and through the murder of Duncan.

Out of this dynamic, Branagh gives a poignant reading to one of Macbeth's lines after the Banquo banquet ghost scene. The Macbeths, alone, sit at the table as he discusses his intention to visit the Weird Sisters and his next step concerning Macduff. Their manner is one of emotional exhaustion, as any husband and wife trying to come to grips with some great household crisis (such as a layoff, learning your child is doing drugs, falling victim to a financial scam, or murdering your king in your home). When she urges him to sleep, Branagh's expression turns dismissive and disgusted. "Come, we'll to sleep," he says sarcastically. "My strange and self-abuse is the initiate fear that wants hard use," and he twirls his crown across the table while giving his wife a look that says, "this is all your fault, but I'll never say it." "We are yet but young in deed," he says, getting up and walking off by himself. A Macbeth and Lady Macbeth who are, essentially, no different than you and your spouse in your passionate ambition for each other bring this play's themes unsettlingly close to home.

Above, Macbeth (Kenneth Branagh) can hardly contain himself upon returning from the wars and a fortuitous meeting with the Weird Sisters and seeing Lady Macbeth (Alex Kingston) who presses his letter to her against his chest. Below, Duncan (John Shrapnel) pretends to concede his crown to the invading army in a rain-soaked battle during the opening sequences of Macbeth at the Park Avenue Armory. Photos by Stephanie Berger, Park Avenue Armory.

The timing of this scene is important, too, in that it comes not after Duncan's murder but Banquo's. In most productions I've seen, the act of regicide is the play's turning point, when the Macbeths begin spiraling into psychopathic behavior. This production makes Banquo's tragedy its centerpiece moment, achieved, in part, by depicting him as much older than Macbeth—more like an uncle than a peer—and through the entrancing performance of Jimmy Yuill. His Banquo regards the Weird Sisters in a humorous vein, though he's intrigued by what they say, but when he senses that Macbeth might be regarding them too seriously, he offers some advice: "Oftentimes, to win us to our harm, the instruments of darkness tell us truths, win us with honest trifles, to betray's in deepest consequence." Banquo is dead-on-right on that one, isn't he? Macbeth finally sees how right he is when Banquo's ghost appears, bloody and staring at him not just accusingly but questioningly—"Why?"—and even in a manner that seems to say "You stupid git."

"If thou canst nod, speak too," Macbeth yells at the ghost. "Thou has no speculation in those eyes which thou dost glare with." Though the ghost never speaks, Macbeth understands its meaning: Macbeth had his friend, mentor, and essential wingman in combat—innocent in everything except that he had a son—needlessly slaughtered. Macbeth encounters the ghost almost immediately after learning that Banquo's son escaped the attack, so the vision, seen only by him, condemns Macbeth to the knowledge that the prophecy of Banquo begetting kings remains intact. Macbeth can't change fate.

And so he gets up from the dining table intending to visit the Weird Sisters and find out what fate still has in store for him. His wife is no longer a factor. Her husband's love seems to vanish in an instant, and he thereafter closes himself off to her. She can't handle that.

"All our yesterdays have lighted fools the way to dusty death," Macbeth says in his meditative eulogy upon Lady Macbeth's death. This famous passage, like Hamlet's "To be" speech or Prospero's "We are such stuff" speech, can be a great stand-alone passage and is often delivered in that manner in the play. But in this production it is coming from a man whose overflowing well of passion and love had become bone dry because he and his wife didn't know how to tap the flow, and Branagh's delivery is as haunting as you'll ever hear this speech given.

It also signifies a change in Branagh's Macbeth: He had been manic in his tyranny and defiance; henceforth, he merely goes through the motions, knowing his inevitable demise is approaching at the hands of some man who is not born of woman; knowing that Macduff will somehow be an instrument in that fate; and knowing, most of all, that without the great love he had known, his life has become "a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing."

____________

Kenneth Branagh in "Macbeth"

The Bottom Line: Fasten your kilts and sporrans, it's going to get nasty.

Kenneth Branagh stars as the murderous thane, with Alex Kingston as his ruthless consort, in this vigorous staging of the Scottish Play, directed by Branagh and Rob Ashford.

NEW YORK – Kenneth Branagh first made his mark as a screen director with his pared-down yet robust 1989 version of Henry V. His film output since then has ranged with varying success from personal projects like Peter's Friends through further Shakespeare adaptations to giant popcorn odysseys like Thor. This sensational environmental stage production of Macbeth, which Branagh stars in and co-directed with Rob Ashford, is in many ways a logical culmination of that eclectic experience -- a medieval, mystical blockbuster that combines superlative, fuss-free classical theater acting with muscular storytelling, visceral physicality and propulsive rollercoaster pacing. Oh, and lots of mud.

The production was jointly commissioned by the Park Avenue Armory and Manchester International Festival, premiering last July in the intimate confines of a de-consecrated church in that Northern English city. Reconfiguring their site-specific staging for the Armory's massive, 55,000-square foot Drill Hall, the directors and a brilliant design team led by Christopher Oram have created a traverse stage flanked on two sides by steeply raked spectator stands. A Middle Ages jousting tournament would look right at home here. But the immersive aspect kicks in even before we get there.

Upon arrival, the audience is divided into clans and split off into various rooms showcasing military history. A glass or two of wine is served before druids in hooded cloaks carrying flame torches usher us along a path through the eerie haze of a vast, dirt-floored moor. At one end of the actual playing space, Oram has sculpted imposing Stonehenge-like monoliths, while at the other, Lady Macbeth (Alex Kingston) stands with her back to the incoming crowd, silently invoking the spirits at an altar of votive candles and weathered frescos.

The opening battle -- during which Branagh's Macbeth and his men successfully crush an attempted rebellion against Duncan, King of Scotland (John Shrapnel) -- takes place in a downpour that turns the field to mud. Making remarkable use of the sprawling performance area and the audience's proximity to the actors, the violence of the sword- and dagger-play gets the drama off to a thrilling start -- so much so that the front-row patrons probably don't even mind getting a large mouthful of rain spat in their faces by the victorious Macbeth.

It seems inconceivable that despite a distinguished theater career that began in his native Northern Ireland and has continued uninterrupted in the U.K. for three decades, Branagh is only now making his New York stage-acting debut. Not only is Macbeth an ideal role for him, with his ginger head, ruddy handsomeness and steely gravitas, but at 53, he’s also the perfect age to embody a warrior hero making a furious grab for power before his time is up. Branagh's Macbeth is not a man given to thoughtful reflection but to instinct, action and increasingly, to fear and involuntary glimmers of conscience, making him a surprisingly human tyrant.

In an intermission-less production that rarely pauses for breath during its two-hour duration, the usurper's jockeying for throne and title has been stripped of politics and reason, and de-intellectualized into something closer to raw pagan lust. There's no doubt that this Macbeth is in carnal and emotional thrall to his manipulative wife -- he can't keep his hands off her when he returns from the battlefield. But there's also something almost primal driving his characterization from within, an innate force of darkness fed by the cryptic prophesies of the Weird Sisters.

Played by Charlie Cameron, Laura Elsworthy and Anjana Vasan, the witches are an uncommonly nubile trio here, darting around like snickering J-horror waifs, with their eyes glowing and their bodies writhing in orgiastic pleasure through each new bout of bloodshed. Their "Double, double toil and trouble" incantation is delivered in a state of convulsive possession, as they conjure a churning human soup out of flames.

Fluidity and urgency are the production's keynotes, frequently amplified by the pounding of composer Patrick Doyle's war drums. Testosterone runs high throughout, even extending to Kingston's driven Lady Macbeth. Playing against the soft womanliness of her physical appearance, the former Royal Shakespeare Company member draws a circle around herself in the earth in her "Unsex me" soliloquy. With that gesture she liberates her capacity for male cruelty to a degree that both beguiles and frightens her husband, while also triggering her gradual descent into insanity. From the moment she persuades Macbeth to seize his chance and kill the King while he's sleeping under their roof, the couple's fate is sealed, even as they shrink from it in terror or madness.

Theatergoers who insist on poetic oratory and subtle textual exploration might be resistant to Branagh and Ashford's bold directorial approach. But this is a riveting staging, unblinking in its lucidity as it exposes the ugly essence of power and brutality with a starkness that makes it impossible to look away. Just the use of the long corridor-like performance space alone is mesmerizing, often requiring the quick attention shifts of a tennis match.

The large ensemble contains no weak links. In addition to the exciting central performances of Branagh and Kingston, Richard Coyle's ruggedly masculine Macduff is notable, and his shattered discovery of the murder of his wife (Scarlett Strallen) and son (Dylan Clark Marshall) is among the play's most wrenching moments. Jimmy Yuill is a warmly avuncular, almost Falstaffian Banquo, which makes his apparitions as a bloody ghost all the more startling. Shrapnel brings effortless authority to the doomed King, and Alexander Vlahos as his orphaned son effectively shakes off any trace of callow youth as he finds his noble calling.

Stunning stage pictures punctuate the production, bathed in the piercing shafts of Neil Austin's sepulchral lighting. Among them is the disturbing image of the witches, who at one point appear to levitate between Oram's stone pillars (pictured below). The funeral procession for the slain King is an affecting moment of pageantry amid the barbarism. Similarly beautiful in its choreographed formality is the advance of Birnam Wood to Dunsinane Hill, with soldiers hidden behind shields made of tree branches. And Macbeth's vision of a dagger before him brings a flourish of dark magic that echoes the play's supernatural elements.

The production's most resonant effect, however, is illustrated in a lament spoken with stirring depths of feeling by the nobleman Ross (Norman Bowman), for a country that "cannot be called our mother, but our grave." Even after tyranny is vanquished and peace and justice restored, the sorrow of death hangs like a thick mist in the air.

Park Avenue Armory, New York (runs through June 22)

Cast: Kenneth Branagh, Alex Kingston, Richard Coyle, Scarlett Strallen, John Shrapnel, Alexander Vlahos, Elliot Balchin, Jimmy Yuill, Patrick Neil Doyle, Edward Harrison, Norman Bowman, Andy Apollo, Dominic Thorburn, Nari Blair-Mangat, David Annen, Harry Lister Smith, Charlie Cameron, Laura Elsworthy, Anjana Vasan, Dylan Clark Marshall, Katie West, Benny Young, Tom Godwin, Stuart Neal, Jordan Dean, Cody Green, Zachary Spicer, Kate Tydman

Directors: Rob Ashford, Kenneth Branagh

_______________________________

JUNE 4, 2014

Photo by Stephanie Berger/Park Avenue Armory

Kenneth Branagh and Rob Ashford’s production of “Macbeth,” premièring in the U.S. on June 5th at the Park Avenue Armory after a sold-out run in Manchester, begins with an epic, visceral battle scene that takes place on a dirt stage: rain pours forth from the heavens, thunder rocks the air, swords clash and sparks fly, actors bellow, mud spatters.

“I was given a note by the director yesterday,” Jim Leaver said, on the morning before previews began last week. Leaver is the production manager, and he was kneeling in the cavernous fifty-five-thousand-square-foot Drill Hall where the play is staged, running a handful of dirt through his fingers as the tech team tested out the speaker system. He cleared his throat and raised his voice to be heard over the sound of brandished swords, cracks of lightning, and “Star Wars”-esque bloops echoing around him. “He said it wasn’t ‘puddly’ enough.’ ”

He was referring to Ashford, who has received eight Tony Award nominations, one Tony, and one Olivier, and was standing in the Armory’s entryway, clad in jeans and a checked shirt and holding his notebook. He opened it to show the negative note—“No puddles!”—scrawled on one page, then made an attempt at clarification: “To play the post-battlefield scene, it’s more profound to have puddles, to have murdered bodies lying there in the puddles.”

The Goldilocksian task of making the mud just puddly enough falls to Leaver, a white-haired, jovial man whose British accent lends his filthy talk an air of sophistication. He has been immersed in “Macbeth” mud for more than a year. During tech rehearsals in London last summer, he began experimenting. “We took chopped wood and soil and had at it with watering cans,” he recalled. “It looked like it was puddling nicely and wasn’t too slippy, which is what we’re trying to achieve here. Nice puddling, minor slippiness.” Alas, as tech week progressed, the soil started to coagulate. “It wouldn’t drain, so we had the actors in mud up to their knees. We did some soul-searching,” he said.

He and his team landed on an “optimal mud recipe”: three parts finely ground bark to one part builder’s sand, which keeps the mixture from binding together and aids in water drainage. Christopher Oram, the set and costume designer, called it “a brilliant solution. You get the quality and sensuality, but it’s also playable. And it smells peaty. That’s key.”

In Manchester, less for authenticity’s sake than for logistics, the components came from Scotland. Manhattan’s version of the Scottish play will be performed on North Carolinian soil. On Memorial Day weekend, a truckload of fifty-two cubic yards of mulched pine bark and seven cubic yards of sand travelled north. About half of it was dumped onto the Armory floor. “We loaded it in the American way, with big, burly guys,” Oram joked. “The British way was effete, with wheelbarrows.”

Every day, a team of three crewmembers is in charge of mud maintenance. It is raked and turned over entirely on alternate days.

In Manchester, the play was performed in a deconsecrated church that held about two hundred and eighty people. Though the production setup is mostly the same in New York—a center “trough” of stage running between two sets of stadium seating—the Armory production is on a larger scale. Faced with excess space, the directors decided to tack on a vast indoor heath, which the audience members, four times as many as in England, must walk through to get to their seats. The Armory, with interiors designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany and Stanford White, was built by the National Guard’s Seventh Regiment of the Civil War—known as the Silk Stocking Regiment due to its upper-crust New York membership. The building served more as a social hall than a military one. Over the years, its Drill Hall has held such events as the lying-in-state of Louis Armstrong and a production of the New York Philharmonic that involved three orchestras surrounding an audience. The space is tailored to each performance, mostly from the ground up.

In the case of “Macbeth,” this involved two key considerations: how to prepare the space for a nightly rainstorm—the set-production team built a ramped floor on top of the existing one, outfitted it with a waterproof pond liner, and topped it with an outdoor-flooring product, a layer of black carpet to insure that only water filters through, and then, finally, the earth—and how to make it rain.

Two cubic yards of heated water—“like a bath, so the actors don’t get ill,” Leaver explained—are sanitized with pool chemicals, then pumped up four stories, into the forty-foot pipe that hangs from the ceiling, where it is released from nine jets. “You have to finesse it a bit,” Leaver said. “It’s twice as high as it was before, so the first time we tried it, the first two rows got absolutely soaked.”

After filtering through the mud, the rain runoff drains into a tank underneath the seating structure, then is pumped through a tube to the dressing room and flushed into the sewer system. “We’ve put a bit of ladies’ hosiery over the end of the tube to catch any mud clumps,” Leaver said. Lest the New York sanitation system be alarmed, he deemed the water “cleaner than what comes out of your toilet, you know, with the papery bits and all that.”

A seven-hundred-and-twenty-square-foot dumpster is standing by on Sixty-sixth street, between Park and Lexington Avenues, for dirt fill-in as the production winds on and the mud is depleted. Actors trek it out through the dressing room—the wardrobe department stays late every night to launder the dirty costumes, giving new meaning to Lady Macbeth’s utterance as she descends into madness—and some inevitably is washed out in the water. And there’s yet another cause of mud reduction. “When you have thirty guys charging through the battle in this earth, the audience needs to be expecting to interface with the, shall we say, earthly qualities of the show,” Leaver said diplomatically.

In other words, if you’re sitting in the first few rows, expect to get dirty.

_______________________________________

'Macbeth,' Scotland Included

By Stefanie Cohen

Creating a Mini Scotland in a New York Armory

The production starring Kenneth Branagh spreads through a New York armory and includes a heath, a henge of stones and a large mud pit.

Painter Richard Nutbourne hopped off a flight from England last week and headed straight to the New York's Park Avenue Armory to check that the nearly two dozen giant artificial stones he had shipped over the ocean had arrived safely. "They look a little small in here," he said, dusting off some loose dirt from the 19-foot high slabs of polystyrene and fiberglass with a plaster finish. The rocks had survived the trip virtually intact. Indeed, the 80-foot-high ceilings of the Armory did dwarf the slabs—not unusual for productions playing inside the castle-like structure completed in 1881 as headquarters for the National Guard's Seventh Regiment. But Macbeth costume and set designer Christopher Oram wasn't concerned. "You don't want them too big," he said. He emphasized that the stones needed to be part of the "human scale" of the set for the new production of "Macbeth," starring Kenneth Branagh in his New York stage debut. The show opens Saturday at the Armory.

The set is as ambitious as the play's main character. It features a giant slab of Scottish heath along Park Avenue, where Macbeth will wage battle against rival clansmen and, ultimately, himself. The full-size "stones" form a henge at one end of the stage. There's a 20,000-square-foot heath through which audience members will traipse to get to their seats, at the far end of the 55,000-square-foot Drill Hall. Once ticket holders arrive at the stage area, they will climb into rough-hewed wooden bleacher seats on either side of a long narrow pit filled with dirt. During the first scene, it will rain, which will turn the dirt into mud. In this mess, at intervals over the next two hours, clans of Scotsmen will attempt to bludgeon each other to death inches away from the front rows.

"We wanted to present a 'Macbeth' that will be visceral and aggressive and masculine and frightening, and yet also addresses the poetry of the writing," says Mr. Oram, surveying the transformation from Drill Hall to heath. Over the course of 10 days, between 75 and 100 men and women labored to create the massive set. As opening night neared, men outfitted in mountaineering harnesses hung like spiders from the giant metal frame of the bleachers they were constructing; their clanging sounded like swords clashing. A team of workers fabricating the heath rolled gray paint onto the floor, while another group separated moss into clumps. The stones themselves—painted by Mr. Nutbourne with gesso, plaster, bits of seashell, pumice stone, granite and sand—loomed in the center of the hall as if dropped there by prehistoric Upper East Siders.

Co-directed by Mr. Branagh and Rob Ashford, this version of "Macbeth" is the third major production in the past two years in New York. "We wanted to embrace the Armory space, and use the entire room, not deny it," says Mr. Ashford, who co-directed the play at Britain's Manchester International Festival last summer, where the sold-out production won raves from critics. At the festival, the actors performed in an old church with a mud pit stage built into its center. At the Armory, the creative team wanted to keep the intimate scale of the church stage. The challenge was to fill the rest of the space. That led to the idea of the heath, a swampy patch of land with shrubs, moss, grasses, puddles and hillocks. A custom-made ancient, mossy "paved stone" pathway runs through the heath, which will lead audiences metaphorically away from the city and into the pagan, earthy world of the play, in which three "weird sisters" predict characters' fates.

To make the heath, Mr. Oram commissioned New Jersey scenic shop Infinite Scenic. Co-owner Valerie Light and her design team first laid down a carpet over the floor to protect it. Then Ms. Light's crew placed plaster molds and pieces of clear plastic on the carpet which would turn into small mounds of earth and puddles. They interspersed grasses in clumps over the floor. Then six men in plastic suits (to keep from getting dirty) and dust masks drove a diesel truck into the hall via a garage door on Lexington Avenue. They fed a container on the truck with a sound-absorbent and natural fiber insulation product called K-13. They mixed it with water and glue, so it resembled cold, gloppy oatmeal, then sprayed that brew over the floor with a fire hose, forming a muddy carpet of sorts. A team of scenic designers followed behind, raking the muddy mixture into what would resemble earth and dirt; the muddy carpet dried in that shape. "I've never made a swamp before," said Ms. Light. At the end of each performance, the "rainwater" seeps through the stage mud into a trough below the stage that feeds into a reservoir, draining the stage so it's fresh for the following day. Shakespeare didn't write stage directions into his plays, an absence that freed Mr. Oram to let his imagination run wild, he said. "This is all out of my head. It's a little insane," he said. "Actually, it's a lot insane."

___________________________________________

Michael Grandage of the Donmar Directs Jude Law in Hamlet at the Broadhurst on Broadway

It's a mouthful. But so is Shakespeare. And the lead here is that you can understand every word Hamlet utters in Jude Law's clean and crisp rendering of what can be an earful to modern audiences. Accessible, yes. Even to Americans, and yes, even to tourists. So, kudos on that score.

Jude Law was good in Hamlet--yet not great. Perhaps it’s not fair to say that one of theater’s most cherished icons was “not fully realized”. How can an actor be all things inside and outside of a character? The answer, of course, is that one can’t, and mustn’t: there is your version of this person, and the question becomes whether your interpretation is fully realized for the audience.

When doing Shakespeare this can be doubly tricky for an actor because of the verse. Will the audience buy it? Will the audience believe it? Law gave us an excellent physicality, but I felt it was almost as if he were leaning on that to capture all of Hamlet--which resulted in a "performance" as opposed to a more intimate wrangling with such a complex young man. He absolutely captured Hamlet's youth and quick-tongue, and his lean lithe figure was beautiful--more beautiful than anyone else on stage, whichever gender. However, Law's verbal facility (assured and considerable) had a tendency to hijack Hamlet's richer soul, tortured or in grief. Perhaps it was used as a mask, worn over the soul, but we long to unlock the mystery. A key element in making me believe

in Hamlet is the deep sense of grief he should feel for his dad, and I didn't get a wink of it from Law.

As another review mentioned, this Hamlet was in control virtually all the time.

So his decision doesn't come off as a decision, the mousetrap is window dressing,

and he's more hero than Hamlet.

The lighting and staging I found to my taste, though some reviewers say it's

vintage Grandage -- the concentrated shafts of light (which I very clearly

remember from Grandage’s “Richard III” in Sheffield with Kenneth Branagh), the brick background. But the opening and closing of huge doors (very Branagh Henry V-like and as impressive) felt as if Elsinore were a prison, and that this was the palace which Hamlet experienced, as opposed to the palace which in fact existed. The clothing choice--I can't in fairness call it costuming--was as my son

called it, "AmApp"--meaning American Apparel basic grey and more grey

and black for some contrast. The choices did not add to any aspect

of the production, and the stills of Law make him look like an advert in the

Sunday Times magazine.

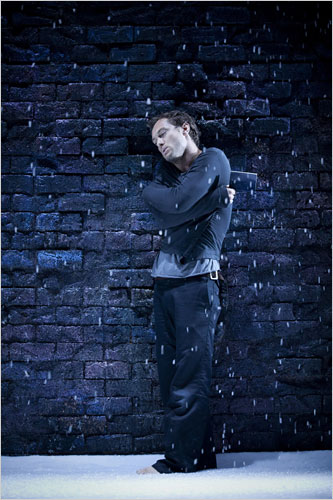

Some critics say they were distracted by the snow—to that I say, “Oh c'mon!”

The gentle blue-lit snowfall was a setting worthy and instantly memorable for the most famous monologue in the world. The analogy of a life as brief as a snowflake, where each may appear to float in a flurry of frost, but is in fact hurtling to the ground, is beautifully tragic. It also looks awesome. And while you can complain that Law not only seems remote, but is literally distant from the warmer bodies straining to hear this bit, he does move downstage closer to the audience eventually . . . at least I thought he did. It wasn’t a “sit on the edge of the stage, legs dangling” and let us look into his eyes scenario.

Kevin R. McNally as Claudius was good. True, he did not connect during the prayer scene (in Branagh’s film version Derek Jacobi for me is the height and weight of a king in stolen robes.) But McNally’s portrayal was strong, and gave shape and balance to an often underwhelming sense of the court. Ron Cook as Polonius was a scene stealer, and helped the production by giving the audience an actor with whom to connect, although the funny man trope is one which is o’erdone.

Laertes played by Gwilym Lee was not at the level I hoped for, and he was wearing a terrible outfit to boot. Ophelia . . . Gugu Mbatha-Raw had no effect on me; it was as if lines were being spoken somewhere, not grounded in the action or emotion of the moment. I do feel sorry to have to say that. Did I mention that acting is not easy? Geraldine James as Gertrude was fine, though not particularly memorable. But that might have been the pants.

I know Peter Eyre was supposed to be—well, I don’t know what he was supposed to be. To my ears and eyes, he was annoying. His delivery was flowery and totally not of this world—and I don’t mean that in a good or even ghostly way. It irked in the faux posh cadence of many a lesser thespian. Oy, sorry!

The scarcity of props and doodads brought the acting into clear focus, which is both a gift and responsibility for the cast. I don't remember music, or pointed use of sounds--these seem like areas which can help pull us further into the production, but not put to use here. I don't remember silence being used as a punctuation mark, either.

Law acquitted himself without looking foolish, or making it an empty vanity piece. The shame is that he did not pull off a major coup; I feel like Law has more untapped than he was able to dig for.

The night flew by, the pace was good, and in no time at all the play was nearing its end. I wanted it to go on, so I must have been enjoying myself. So there.

The finale foil work was sharp, and spirited, and someone in the audience actually

gasped when Gertrude grabbed the cup. Even a tough New York audience can be adorable.

Ralph Fiennes continues to vary his career, choosing to return

to the stage again, under the direction of Jonathan Kent with the Almeida Theatre productions of Richard II and Coriolanus.

After the scheduled run at Gainsborough, the productions will move

to the Brooklyn Academy of Music venue in New York in the fall.

Tickets for the BAM performances are on sale as of April 1, 2000, and

may be ordered online at the BAM website. Order soon,

as available seats are disappearing.

***************************

London's Tiny, but Mighty, Almeida

London -- As a theater reporter for The Times of London wryly wrote the other day,

"The Almeida's bid for world domination progresses apace"; and that seems no great

exaggeration. Right now, the tiny but hungry playhouse is reaching out from mission

control in North London to colonize a bit of East London, a bit of Central London,

eventually a bit of New York, and, if NASA ever opens up the planetary system to space

thespians, one day no doubt bits of the Moon or Mars or both.

If we discount the much-hyped London debut

of Kathleen Turner in a stage version of "The

Graduate" -- of which more in a moment -- the

Almeida has been gobbling up the London

critics' attention in recent weeks. First there

was the premiere of Harold Pinter's

"Celebration" at the company's grungy

headquarters in Islington. Then it presented

Nicholas Wright's new "Cressida" in the West

End, with a magnificently dilapidated Sir

Michael Gambon as a trainer of the boy actors

who took female roles in early-17th-century

England. And now it has reopened the doors of

the East End film studios once used by Alfred

Hitchcock and staged "Richard II" with Ralph

Fiennes as the king, a production expected at

the Brooklyn Academy of Music, along with

"Coriolanus," in early September.

'Richard II'

The Almeida has a habit of dispatching major

performers across the Atlantic. Mr. Fiennes as

Hamlet, Diana Rigg as Euripides' Medea, Liam

Neeson in David Hare's "Judas Kiss," Kevin

Spacey in O'Neill's "Iceman Cometh": all have

appeared in the company's productions in New

York, the first two of them picking up Tony

Awards for their pains. But most artistic

exporter-importers would not regard "Richard

II" as an especially valuable addition to that

inventory. Shakespeare's inept English king is

not, after all, as massive a creative challenge as

his emotionally turbulent Danish prince. The

surprise at the Gainsborough Studios, then, is

that Mr. Fiennes finds almost more in a lesser

role.

Actually, it's a double surprise, since there is

something about that elegant profile that makes

you half-expect a reprise of the graceful,

willowy, vocally exquisite Richard with which

John Gielgud established his importance in

London 70 years ago. But barely has Mr.

Fiennes been ferried onstage in his glistening

white robe and glistening white throne than

he's suggesting why almost all the English

nobles will be delighted to see him lose his

crown to the usurping Bolingbroke.

He uses his thin smile either to mock them or to

seek reassurance from his flatterers, and his

tongue to flaunt his wit or, at one bizarre point,

to stick out and wiggle at his angry uncle, John

of Gaunt. He is disdainful, petulant, malicious

and smug.

But there are political as well as personal

reasons for dethroning him. Mr. Fiennes's king

is clearly improvising public policy as the whim

takes him, whether that means taking charge of

Irish wars, banishing dangerously influential

men, raising taxes, anything. He seizes the

exiled Bolingbroke's lands while picking the

petals off a flower, and just as casually. Never

have I seen a Richard II who made me so aware

of how quick and quixotic his key decisions

are, and I have seldom seen a production that

so lucidly posed a question still alive when

Shakespeare wrote: is there a point when

mortals are entitled to depose God's deputy on

earth, the divinely anointed king?

Jonathan Kent, who directs, brings energy and pace to a play that can seem a classroom

slog, getting good supporting performances from Linus Roache, a Bolingbroke with the

resolution and the sureness of political touch that Mr. Fiennes's Richard lacks, and Oliver

Ford Davies as a Duke of York less torn than dismembered by his conflicting loyalties. But

in "Richard II" it's the title character who matters, and, despite his unsentimental

interpretation and coldly chiseled profile, you couldn't call Mr. Fiennes inhuman or finally

unsympathetic.

Yes, he displays a self-infatuated glee when he steals Bolingbroke's birthright, and, yes, he

thrusts his head forward like a venomous cobra when he rejects a man he pretends to love.

But adversity brings out more than just self-pitying bluster and manic mood swings. There is

unexpected majesty in Mr. Fiennes's outrage when, high on a balcony, he confronts the

rebels. There is a moving realism in his recognition that "I live with bread like you, feel

want, taste grief, need friends." And there is a mournful wisdom when, alone in his prison

cell, he confesses that "I wasted time and now doth time waste me." Even arrogant,

unself-knowing despots can grow -- and Mr. Fiennes's Richard proves it.

***************************

London Times

Benedict Nightingale sees the Almeida deliver a triumphant Richard

II

This happy breed of actor

For a man with a profile that might

have been chiselled for display on

some new Parthenon by a

contemporary Phidias, Ralph

Fiennes is a surprisingly flexible and

versatile actor. Here he is in the

vast, vaulty Gainsborough Studios

in Shoreditch, a mix of old brick,

timber, scaffolding and black

foam-rubber seats where Alfred

Hitchcock shot several of his

movies, playing Richard II for the

Almeida, the same company that

staged his fine, courtly Hamlet five

years ago; and somehow he

succeeds in giving a more various,

multi-coloured performance in what

everyone would agree to be a less

rich and rewarding part.

In he comes, borne on a white

throne as on a sedan chair, right up

to the rectangle of tufty grass that

serves as a stage and presumably

symbolises "this blessed plot, this

earth, this realm": ie, the England he

has omitted to keep properly tended

and mown.

Notwithstanding the peculiar yellow cycling trousers just visible beneath

his shimmering gown, he looks and sounds every inch the monarch. But

then he proceeds to step down, and from that moment we sense the

volatile blend of preciosity, humour, weakness, bitchiness, arrogance,

smugness, sarcasm and sheer folly that eventually loses him his throne to

Linus Roache's Bolingbroke.

In Richard II, more than any other of Shakespeare's plays, a key

conundrum is posed. The king is God's representative on earth,

untouchable. He is also a man, fallible. What is to be done when the man

contrives to subvert the divine deputy? Fiennes offers us some genuinely

regal moments, notably when he emerges on a balcony high above his

emblematic slice of England, and with all the charisma at his formidable

command gives the usurping lords an all-too-prophetic warning of the

results of their blasphemy and hubris. But he is far more frequently a

spoilt man with an unreconstructed child somewhere inside him.

After all, what are his subjects to do with a king who skims with such

shallow ease from mood to mood, instant idea to impromptu decision?

For instance, Fiennes's Richard finances his ill-considered Irish wars by

formulating a punitive tax policy in the time it would take Gordon Brown

to take a couple of sips of water in mid-budget speech. And what are the

English nobles to make of his lightly disguised distaste and half-open

mockery of so many of them? He grins at his flatterers, he waggles his

tongue at the dying John of Gaunt, he seizes the dead man's goods while

he casually picks and discards petals from a flower. Beside him,

Roache's Bolingbroke, incisive yet not insensitive, strong yet deeply

troubled by the close of the play, is in every respect but the divinely

sanctioned one the better equipped to rule.

Jonathan Kent's production is brisk and pacey, and offers especially good

supporting performances in Oliver Ford Davies's flummoxed York, a

not-very-good swimmer trying to maintain equilibrium in a tank of

warring piranhas, and from David Burke's Gaunt, who not only gives his

famous elegy for England the political significance it demands but

transforms it into a pained and wistful lament for his own imminent death.

But finally any Richard II must be judged by its Richard II, and in the

play's later stages Fiennes moves beyond imperious bluster, mandarin

self-pity, toffy-nosed ire and all such things.

In his prison he is, as he should be, a man but no longer the same sort of

man. There he stands, alone in a thin yellow light, occasionally

succumbing to bitterness, yet also mournfully but carefully enunciating

the simple syllables in which he acknowledges his blasted aspirations and

wasted life. He seems physically to have withered - but also to have done

what Shakespeare wanted. He has grown.

***************************

The Express

Sam and Ralph are the men

who would be King Richard

By one of those strange theatrical

coincidences, two brightly burning lights of

British stage and screen are going head

to head in productions of one of

Shakespeare's less performed history

plays.

Ralph Fiennes for the Almeida Theatre,

and Sam West for the RSC in Stratford,

will be offering their takes on Richard II,

the Plantagenet king who was deposed

and murdered in a 14th century coup

d'état.

Fiennes alone would be enough to attract

interest. Buoyed by a series of fine

celluloid performances in The End Of The

Affair, Onegin and the forth-coming

art-house epic, Sunshine, Fiennes is not

only a star but an actor of physical and

intellectual gusto.

But the added tang of having 30-year-old

West in a rival performance at the same time has theatrical connoisseurs

intrigued.

While West, son of Prunella Scales and Timothy West, has faded - perhaps

deliberately - from the movie radar since his leading role in Howard's End, he

is a highly sought presence on television, radio and the stage. He has never

been modish like Ewan McGregor or Jude Law, but has quietly established

himself as a pillar of the orthodox acting establishment.

The chance to compare and contrast the two actors' Richards is therefore a

rare treat for fans of such things.

In the Shakespearean version of medieval history, Richard was a watery

dreamer. Given to long soliloquies, he is introspective, poetic and totally

unsuited to kingship. It is a complex part, but not one to cast chisel-jawed

actors in an heroic light.

"That's what makes it interesting," says Kenneth Branagh, a friend of both

men and an actor for whom the works of the Bard are something akin to a

personal fiefdom. "I fully intend to catch both Sam and Ralph doing Richard

as they are both first-rate classic actors.

"The interpretation will be fascinating. I don't think either will be a wimpish

Richard, though the part can be seen as such. Both Sam and Ralph have the

lyricism, both have something of the poet in them and both have the

cheekbones - which I wish I could say myself. But Richard does have a lot to

say and there's skill needed to manoeuvre through the soliloquies."

Although Richard's character is profoundly flawed, it seems that neither of the

actors are prepared to play him as an anaemic drip.

"It's more the case of playing a man totally miscast," says West, who began

rehearsals in Stratford last month. "He is the king forced to play a role he's

completely unsuited for."

But West insists that the play retains a relevance beyond its protagonist's

central human drama. "I can tell people I'm doing a play about poll tax riots,

the Irish question and whether we should be a republic or not, and they'll

assume it's set in 1999 not 1399," he says.

Perhaps for this reason, both productions appear to eschew chain mail and

tapestries for a more contemporary setting.

"We're working in a white minimalist space and I'm pretty certain it won't be

done in medieval costume," says West.

Of Fiennes's production - to be staged by Jonathan Kent in East London's

Gainsborough Studios along with Coriolanus in which Fiennes also stars - a

production insider says: "It's going to have a fairly modern setting - imperial

Austrian, not quite Ruritanian but that sort of thing. The set is a very large

space, which Ralph's a bit concerned about. I think Sam's doing it in a

smaller setting.

"Ralph's going to do a harder Richard than usual, not weepy and wet. It's the

flip side of his Coriolanus. He says they each show a deeply flawed leader,

but if you combined them you'd have the ideal monarch - both aggressive

and ameliorative".

Though comparisons between the two Richards will be fascinating, West is

keen to stress there is no professional rivalry between the pair. "I don't like

the idea that we're in competition with each other because of course we're

not," he says. "In fact, I've already delivered a card to the theatre. It says, 'I

hear we're both going to be playing Richard. Good luck to us both'."

Richard II at RSC Stratford (01789 403403) from March 20; Richard II at

Gainsborough Studios, London N1 (0171- 359 4404) from March 30.

(Thanks to Claire and Ngoc, and to Isabel, Georgiana and Claire for the photos.)

For a back issue featuring

Rufus Sewell as Macbeth, click

here.

Editor-in-Chief

The Daily Telegiraffe

Let not light see my black and deep desires.” – Act 1, Scene 4.

Spectacular Shakespeare

Eric Minton

June 13, 2014

The Hollywood Reporter

'Macbeth': Theater Review

6/5/2014

by David Rooney

>

Photo by Stephanie Berger

Playwright: William Shakespeare

Set & costume designer: Christopher Oram

Lighting designer: Neil Austin

Music: Patrick Doyle

Sound designer: Christopher Shutt

Fight director: Terry King

Illusion consultant: Paul Kieve

Presented by Park Avenue Armory, Manchester International Festival, in association with Colin Callender

PUTTING THE MUD IN “MACBETH”

POSTED BY SOPHIE BRICKMAN

The New Yorker

![]()

The Wall Street Journal

May 29, 2014

Photo by Andrew Hinderaker

New York Times

23 April 2000

Benedict Nightingale

14 April 2000

staged by the Almeida at Hitchcock's old Gainsborough Studios in Shoreditch. Photographs by Donald Cooper

20 February 2000

Mark Jagasia

![]()

FRONT PAGE

News/

The Good Bits![]()

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE

![]()

THE HAMLET PAGE

![]()

links/LINKS

![]()

What's Up: STAGE

![]()

What's Up: BOOKS

![]()

What's Up: MUSIC

![]()

What's Up: FILM

![]()

Fictional Characters

![]()

What's Up:

ART![]()

Today's Special

![]()

Sure We

Thank You